By Christopher Vecsey, Harry Emerson Fosdick Professor of the humanities and Native American studies in the Department of Religion

Class of 1900, the renowned minister — and author of a famous hymn — Harry Emerson Fosdick was a central figure in American Protestantism of the early 1900s.

1900Professor Christopher Vecsey delivered this engaging biographical, scholarly, and social assessment of the namesake of his distinguished academic chair for the Division of Arts and Humanities Spring Colloquium Series, on April 17, 2018.

Overture

Several years ago, our religion faculty was having its dog and pony show for parents and students on Family Weekend.

Came Q&A, and after a few of the usual questions about the monetary value of studying religions — you know: “What do you do with a degree in Religion?” — one man raised a surprising concern. He asked, “Why is it that Colgate doesn’t pay attention to its most distinguished graduate, Harry Emerson Fosdick?”

I was more than a little chagrined, since I am the occupant of a distinguished chair named in honor of Harry Emerson Fosdick.

I certainly knew who Fosdick had been:

- Born 1878, Colgate graduate, Class of 1900

- Protestant minister, ordained in 1903 after divinity study at Union Theological Seminary

- Pivotal figure in the Liberal-Fundamentalist split in American Protestantism in the 1920s

- Founding pastor of John D. Rockefeller’s ecumenical Riverside Church in Manhattan, 1930

- Author of nearly 50 books and more than 1,000 sermons

- Radio preacher of great renown, from the 1920s to the 1940s

- Indeed, he was surely America’s most famous Christian minister of the 1900s, until the rise of Billy Graham (recently deceased)

In my life, I have had several reasons for a long-standing fondness for Fosdick. First, I loved visiting his Riverside Church on 120th Street when I was doing archival research in the Missionary Library at nearby Union Theological Seminary, for my Honors Thesis at Hunter College in the summer and fall of 1969. Second, I appreciated his pacifist writings — e.g., A Christian Crusade Against War (1923) — as I prepared my case as a conscientious objector in 1970. (I performed two-plus years of alternate service, 1971–1974 in the Big Muddy Vietnam War years.) Third, I love singing, and at Colgate I have been able to get a chance at least twice a year, at Convocation and Commencement, to belt out Fosdick’s lyrics to “God of Grace and God of Glory” — the melody is not his. This has been Colgate’s one major, public celebration of its most distinguished graduate — besides my chair.

God of Grace and God of Glory1

CURE THY CHILDREN’S WARRING MADNESS:

BEND OUR PRIDE TO THY CONTROL;

SHAME OUR WANTON, SELFISH GLADNESS,

RICH IN THINGS AND POOR IN SOUL.

GRANT US WISDOM, GRANT US COURAGE,

LEST WE MISS THY KINGDOM’S GOAL,

LEST WE MISS THY KINGDOM’S GOAL.

A singing of “God of Grace and God of Glory” — whose words were written by Rev. Harry Emerson Fosdick, Class of 1900 — at the conclusion of the baccalaureate service during Commencement Weekend, 1989

Despite these reasons for enthusiasm, I must confess that I did not greet the Fosdick Chair with glee when I received it. I already held another chair, and I associated this honorific to Fosdick with Protestantism of a distant era — not really my thing. I study American Indian religions; I teach about Catholicism and contemporary religious trends. Fosdick didn’t fit my self-image. He seemed rather passé in 2010, a forgotten man in the 21st century.

Well, here I am to make amends to the man. I can’t bring him back to life, but at least I can make the few of you here today remember him for an hour or so.

I am no Fosdick expert. I have read his autobiography, The Living of These Days (1956) and a bunch of his published sermons. Colgate has 30 of his books, most in Special Collections, and I have looked through many of them — The Meaning of Prayer, The Meaning of Service, Twelve Tests of Character. Don’t miss his feisty, anti-Zionist book, A Pilgrimage to Palestine (1927). Today, toward the end of my talk, I’ll focus attention on my favorite Fosdick book, Adventurous Religion and Other Essays (1926), which I think illuminates his faith best of all.

My task here is made easy — maybe too easy — by Robert Moats Miller’s magisterial biography, Harry Emerson Fosdick, Preacher, Pastor, Prophet (1985). For the record, Miller calls Fosdick Colgate’s “most distinguished graduate.”2

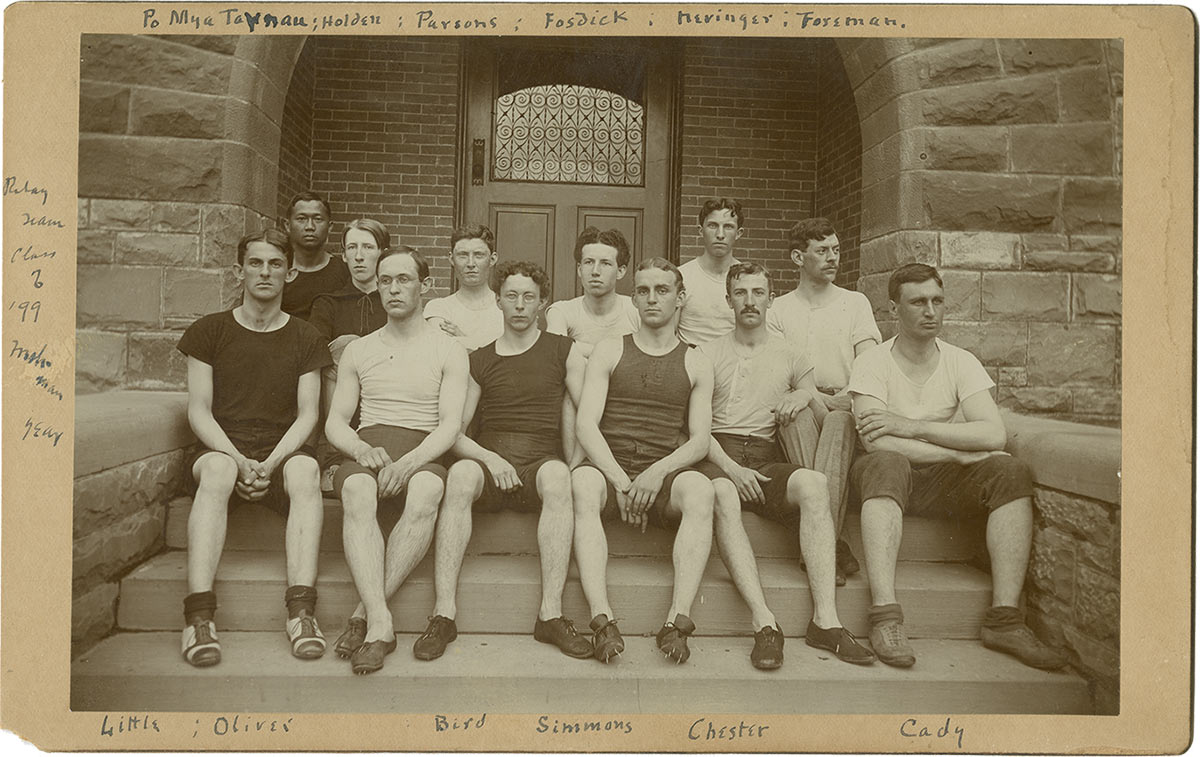

Harry Emerson Fosdick (center, with bushy hair) and his 1899 classmates at Colgate. He took an extra year to graduate, in 1900.

I. Fosdick at Colgate

The son of a high school principal from Buffalo way, Harry took the train to Utica, then another train to Hamilton in September 1895.3 Our college was already called Colgate University by then: 150 students, 15 faculty (not counting the Seminary [6] and the grammar school Academy [6 more] staff). Harry edited the Salmagundi yearbook in his junior year. In senior year, he was editor-in-chief of the student newspaper, the Madisonensis. He was a member of D.U. fraternity, a “Big Man on Campus,” full of “cockiness,” it is said, with an “exuberant” personality. He sang, he danced, he dated, he led cheers, he engaged in frat pranks. He also won a couple of major prizes for oratory: $40 and $60, about equal to a year’s tuition back then. I might add, he graduated first in his little class of 40, summa cum laude, Phi Beta Kappa.4

Raised on religion — Baptist, but with worship at Presbyterian and Methodist churches — he was fully immersed for baptism at age 7. As a youth, he said, “Fire-and-brimstone preaching” affected him mightily and he recalled “weeping at night for fear of going to hell, with my mystified and baffled mother trying to comfort me.”5

So, he entered Colgate a pious teen, taking “for granted the literal accuracy of the Bible as sound science and history.” His Colgate years, however, were a “revolt Against Orthodoxy,” he wrote, where he came to realize, “I did not have to believe anything simply because it was in the Bible. How stunning that conclusion was,”6 he exclaimed.

He quickly became “a convinced believer in evolution.” When he tried to shock his family with this pronouncement, his father replied that he had believed in evolution “before you were born.” His ancestors had included heretics, free-thinkers, Underground Railroad activists, socialists, feminists, etc., so Harry’s college heterodoxies caused no great familial concern. Not even when he wrote to his mother in 1898, “I’ll behave as though there were a God, but mentally, I’m going to clear God out of the universe and start all over to see what I can find.” For a while, he remembered, “wild horses could not have dragged me into church.”7

I did not have to believe anything simply because it was in the Bible. How stunning that conclusion was.”

Harry Emerson Fosdick

This “mental struggle” didn’t last long. No thoroughgoing campus materialist, he admitted, “I was beginning to doubt some of my doubts, ... questioning my questions.”8

This religious disquiet suffused the campus in the 1890s, as Madison University became Colgate. “Passion for knowledge” was edging out moral training as a pedagogical goal.9 The sciences were in ascendancy. Philosophy emerged as a department in 1890.10 The Divinity School had its progressives, notably Prof. William Newton Clarke, whose lecture notes were published in 1894 as an Outline of Christian Theology. (Colgate has this and seven other publications of his in our library.)11 But teachers at the Seminary could go too far in their research. Witness the 1896 dismissal of Prof. Nathaniel Schmidt, for denying the inspiration and inerrancy of the Bible, and for employing scientific methods of biblical criticism. Schmidt quickly found a home — indeed, a chair in Semitic Languages — at decidedly secular Cornell University, where he achieved a certain prominence as teacher and scholar. Harry was present at Colgate at the time of Schmidt’s dismissal.12

The threat of secularization at Colgate roiled the theological faculty, who recalled nostalgically the decades during which the Seminary trained ministers and sent missionaries worldwide. This consternation would lead in 1928 to the departure of the Seminary to Rochester — becoming Colgate Rochester Divinity School — at which point Colgate became recognizable as the Colgate we know: with a liberal arts curriculum, majors and minors, a required core, or general education, program.13

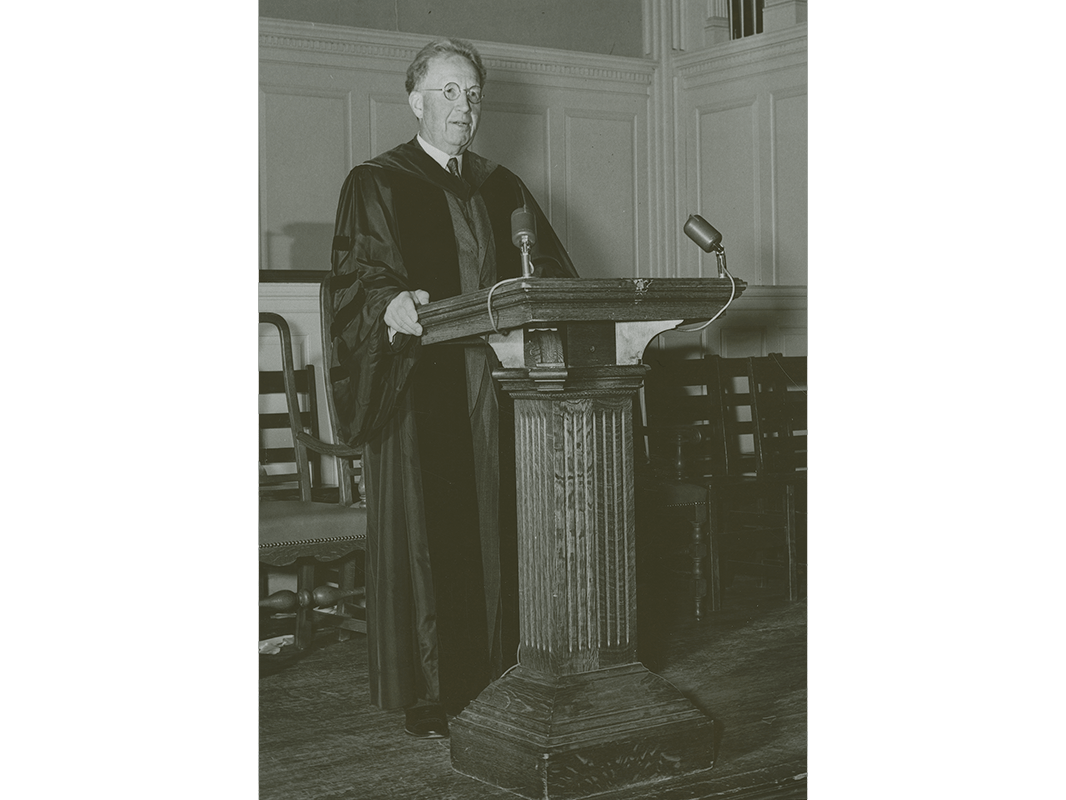

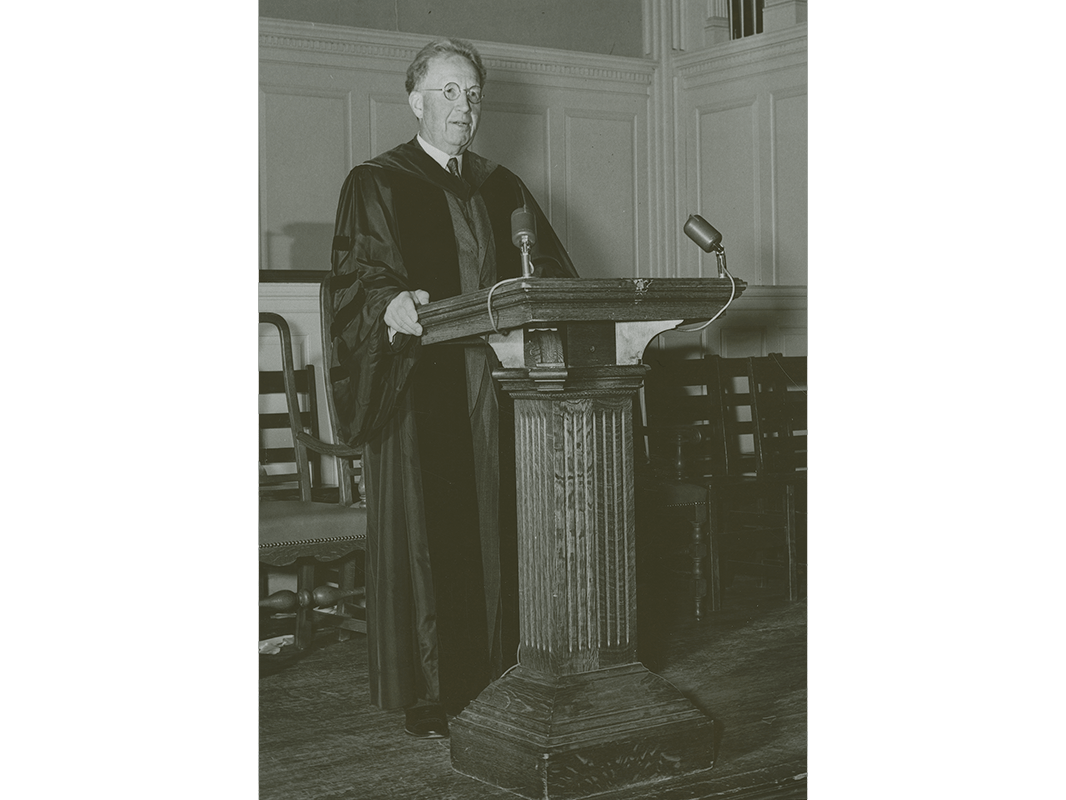

Fosdick in academic regalia, Baccalaureate 1950

Harry came of age at a Colgate that was also coming of age. He found philosophy and science courses “very useful.” At the same time, he reengaged with religion under the tutelage of Professor Clarke. “I was blind, now I see,”14 Harry wrote, and he decided for the ministry as a way of teaching. “Not preaching,” he thought!15

What was Colgate’s effect on Fosdick’s future? Robert Miller states, “The Colgate faculty made it, if not impossible, then certainly more difficult for Harry to have remained permanently in the valley of doubt.”16

In 1953, Fosdick wrote, “I owe more to Colgate than I can ever express.” For all the “smallness of the school and the outward meagerness of its equipment,” as he wrote in his autobiography,17 it shaped his vocation. Colgate’s great strength, he mused, was “the quality of its professors and their personal accessibility to the students.” A professor could become “a friend as well as a teacher.”18

Fosdick, in return, shaped Colgate over the years. He was a trustee for decades and president of the Alumni Association. He attended reunions, gave addresses, assisted in fund drives. He received a Colgate honorary degree in 1914. He was made trustee emeritus in 1956. In 1961 Laurance, Nelson, and David Rockefeller were leading donors to a $300,000 endowment for the Harry Emerson Fosdick Chair of Philosophy and Religion.

Herman Brautigam was the first chair holder, 1961–1969. Please forgive me this litany; these were my beloved elders:

- M. Holmes (Steve) Hartshorne, 1969–1980

- Robert (R.V.) Smith, 1980–1988

- Donald (Don) Berry, 1988–1994

- Jerome (Jerry) Balmuth, 1995–2010

- And me, since 2010

I never knew I was such a Rockefeller tool!

Fosdick attended our Seminary for a year, 1900–1901, but he went on to Union Theological Seminary, and beyond, to fame, however ephemeral.

II. Why His Renown?

In 1904, Fosdick received his MDiv from Union Theological Seminary. In 1908 he completed a master’s degree in political science from Columbia University and began teaching practical theology, Bible, and homiletics at Union. He was already a pastor, with congregations in Manhattan and Montclair, N.J.

He started to write popular journal articles and books based on his sermons, six of which sold into the millions:

- The Second Mile (1908) exhorted its readers to do more than is expected of you, following Jesus’ words and actions.

- The Assurance of Immortality (1913) provided confident Christian apologetics for the afterlife.

- The Manhood of the Master (1913) examined Christ’s character as a model for our own. Fosdick wrote about this book: “My greatest single source of satisfaction, so far as this early book of mine is concerned, is that during one of his imprisonments, Mahatma Gandhi read it. A friend of his saw his copy, well underlined and annotated.” So, Fosdick was gaining an international audience.

Fosdick’s trilogy on The Meaning of Being a Christian — the meaning of Prayer (1915), of Faith (1917), and Service (1920) provided a guide to Christian life:

“Prayer is the soul of religion,”19 which makes God real to us, if we can listen to Him. Faith is the power and commitment to answer “the Master’s call, ‘you can’” with the cry, “‘I will,’” and thus we enter “new possibilities, new powers, and increasing liberty.” Service is “the ethical application of the Christian faith and spirit to . . . social problems.” This is what we might call the Social Gospel.

These books made Fosdick a pastoral phenomenon. He spoke at student conferences and colleges across the United States. By the early 1920s, he was “dubbed the ‘Caruso of preaching.’” A Chicago headline: “Crowds Smash Door: Near Riot to Hear Fosdick.”20

What did he bring, as a preacher that would inspire such fervor? He was not a riotous orator, but rather a calm counselor. Preaching, he said, was “personal counseling on a group scale.”21 As a private pastor, he advised people who were “spiritually sick,” much as a priest does in a “confessional.” (He raised a furor among fellow Protestants with this comment.) As a preacher, he was able to project his “charisma” and empathy to huge audiences, and even over the radio. His style seemed to be “cooperation between religion and psychotherapy.” He was affective, affirmative, but also full of Christian moral convictions. The result was both comforting and challenging. The net result was inspirational to millions.

Crowds Smash Door: Near Riot to Hear Fosdick”

Chicago newspaper headline

A secret to his immense success? In 1902, while studying at Union, living amidst “the raw filth, poverty and degradation” of New York City, anxious about achievement, fearful of failure, Fosdick suffered a bout of “reactive depression” and “utter despair,” and came close to suicide. He received help from his father, and an asylum, but mostly from God.22 “I learned to pray,” he recalled, and God responded to his prayer. “I desperately needed help from a Power greater than my own,” he said. He found it, and this experience galvanized his vocation. Placing a razor to his throat made him keenly aware of the need to help others with their “anxious, devastating problems” through “pastoral counseling” on a grand scale. Close to 2,500 congregants every Sunday at Riverside Church, around three million listeners every week on the radio in his syndicated address, “National Vespers,” in the 1930s and 1940s: he was enormously popular.

For Fosdick, the sermon should lead to a choice. He wrote, “The preacher’s business is not merely to discuss repentance but to persuade people to repent.”23 He closed many sermons with sentences like this: “I want some choices made here this morning.”24

Although Fosdick had no professional training in clinical psychology, his “own suicidal breakdown, he repeatedly claimed, gave him ‘clairvoyance’ into the troubles of others.”25

This talent might be enough to explain Fosdick’s celebrity, but there is much more to tell, about the battle between Fundamentalism and Modernism, and Fosdick’s pivotal place within the arena of contestation that constituted American Protestantism in the 20th century.

Fosdick appeared on the cover of Time magazine in 1930, at perhaps the peak of his fame.

In the face of liberalizing trends within Western culture — historical methods of studying the Bible; rationalistic discourse in higher education; the appreciation of the world’s many religions; the rise of sciences as authoritative analysts of reality; skepticism; materialism; positivism; Nietzschean perspectivism; Marxism, Freudianism; above all Darwinism and evolutionary theory in general — Colgate graduates know it all from the core course Challenge of Modernity — in the face of these revolutions, reactionary Protestants in 1910 declared themselves to be “Fundamentalists,” adhering to a Five-Point doctrinal fundament:

“The inerrancy of Scripture,

Christ’s virgin birth,

his substitutionary atonement

his bodily resurrection,

and his. . . miracles.”

Bent on doctrinal conformity, Fundamentalist theologians declared these five points, and several others added on, like the Second Coming of Christ, to be essential to identity as Christians. To deny any one of them made a person a heretic, a non-Christian, so they avowed.

At the same time, many Protestant churchmen condemned evolution. It clearly offered a counter-narrative to biblical creationism regarding the age and origin of life on earth, including human life. It was a frontal challenge to biblical world view, and this counterpoint led to the crucial Scopes trial in Tennessee in 1925, concerning the teaching of evolution in public schools.

In 1922, Fosdick entered the Fundamentalist-Modernist fray. He preached a sermon that made him more than a famous minister. It made him a culture warrior. Its title asked the question about the kulturkampf of American Protestantism: “Shall the Fundamentalists Win?”

Fosdick rebutted each of the so-called “fundamentals” on rational, historical, and biblical grounds, and he attacked the very notion that “anybody [has] a right to deny the Christian name to those who differ with him on such points and to shut against them doors of the Christian fellowship.”

“Here in the Christian churches are these two groups of people,” Fosdick said — Fundamentalists and Liberals — “Shall one of them throw the other out?” The Fundamentalists, in the throes of “intolerance,” say that “the liberals must go.” Fosdick pushed back: “I do not believe for one moment that the Fundamentalists are going to succeed.” He aimed to oppose them, for if they did succeed, they would produce “the worst kind of church that can possibly be offered to the allegiance of the new generation:” — “an intolerant church.”

Fosdick was the living symbol of Liberalism at arms with the forces of Fundamentalism, and thus his fame, or infamy, depending on your perspective.”

These were strong words. In his autobiography, Fosdick claimed that he was trying to situate himself “near the center”26 of the controversy between Modernism and Fundamentalism — an evangelical, liberal Christian, neither Modernist nor Fundamentalist, willing to embrace both wings of Protestantism. But that is not how his words were received.

Between 1922 and 1924, he was called a “heretic,” a “Unitarian Cuckoo,” a “creedless Baptist”27 unworthy of Heaven or Communion, and surely not the ministry. Conservative Presbyterians said he was not a Christian; his Christ was not their Christ. And they forced him to resign his position as pastor of the First Presbyterian Church in Manhattan, when he refused to assent to its “creedal requirements.”

All of this was front-page news in the 1920s. Fosdick was the living symbol of Liberalism at arms with the forces of Fundamentalism, and thus his fame, or infamy, depending on your perspective.

Full stop, I suppose. But Fosdick’s reputation did not rest with the events of 1922–1924.

With the help of James C. Colgate, Fosdick forged an alliance with John D. Rockefeller, putatively the world’s richest man via Standard Oil, a liberal Baptist interested in creating a non-denominational church in Manhattan, which turned out to be Riverside Church. Rockefeller offered Fosdick the ministry. Fosdick worried what people would think of his being so associated with such a wealthy man. Rockefeller replied, “I like your frankness, but do you think that more people will criticize you on account of my wealth, than will criticize me on account of your theology?”

The covenant was drawn between these dear friends. Fosdick chose the location in Harlem. Rockefeller anted up $10 million, plus upkeep and endowments. The cathedral was built. The building was dedicated in 1930, with the processional hymn, “God of Grace and God of Glory.”

You probably don’t care to hear so much about Riverside Church, where Fosdick presided until his retirement in 1946, but I’ll suggest this to you: Fosdick’s installation in Rockefeller’s cathedral cemented his national eminence as much as his prowess as a counseling preacher, best-selling author, and liberal standard-bearer against Fundamentalism.

So, what was Riverside Church? An “inclusive interdenominational fellowship open to all who ‘believeth in the Lord Jesus Christ.’” Nominally Baptist (i.e., Northern, or American, Baptist, decidedly not Southern Baptist), but also affiliated with the United Church of Christ; 3,500 members, an average attendance of 2,300, just short of capacity, about half of whom were members; the rest were “sermon tasters,” curious auditors. Sunday services were just what you would expect: prayer, sermon, hymns, some silence. Communion on Sunday afternoons; Fosdick was not much of a sacramental ritualist. On other days of the week: fellowship, serious study, social outreach, and much more. If I may suggest, Riverside Church was a “Megachurch” before the term was coined. There was a gym, a school, a refectory, private counseling rooms, but also a dance hall, spaces where men and women could socialize. Fosdick performed thousands of marriages, following his counseling.

Someone once called cathedrals “luxury liners laden with souls.” Riverside seems like such an edifice: a neo-gothic cruise ship where people could engage all aspects of their lives — social, ethical, esthetic, etc. — under the watch of a caring director.

III. Adventurous Religion

We have seen: Fosdick was a Colgate man. He was famous in his day as a Christian sermonizer. But what was the substance of his thought? Did his ideas have an impact that might long outlive him? And if so, why is he so unknown in the 21st century?

Title page of “Adventurous Religion”

My students and I are reading Adventurous Religion and Other Essays (1926), his tenth book. Here is my report, as brief as I can make it.

Fosdick was an embattled thinker, writing in response to “the rise of fundamentalism,” which he saw as something new, a baneful innovation epitomizing dogmatic conformity and sectarian strife.

Religion, for him, was far more than theological creeds and ecclesiastical turfs. It was, rather, “an integral part of a wholesome life,” arising from our elemental needs, and part of our experience. For Fosdick, no one is wholly human without religion, especially the religion of Jesus. Not the religion about Jesus, but the religion of Jesus, the person. Fosdick often said that he believed in God because of Jesus, the person, how he lived, and how he calls us to live. Christian religion is a response to Jesus, a “vital” religion, a “personal adventure on a way of living.”

Dogma about Jesus was abhorrent to Fosdick. Indeed, he refused his entire adult life to recite a Christian credo, like the Nicene or the Apostles’ Creed (although he composed his own creed in 1923). His fealty rather was to “faith,” “a matter of personal venturesomeness,” involving “self-committal, devotion, loyalty, courage.” Fosdick called his audience, as he believed Jesus did — and does — to the “thrill, liveliness and ardor of apostolic Christianity.” Fosdick found this spiritual adventure in “prayer, loving one’s enemies, being sincere, ... repentance, ... inward moral conquest,” building “personal character and social relationships,” and applying the “principles of Jesus to racial, industrial, and international problems.” This was “genuine religion” for Fosdick, not “congealed formulations.”

Fosdick stared down Fundamentalism; he also confronted scientific skepticism about religion: “Why . . . should anybody want to believe in God?” He could see that “contemporary human life, on the one side, and contemporary religion, on the other, have been drifting apart” — a growing secularism. Yet, he felt real religion to be indispensable to “radiant living,” by calling people to develop “moral autonomy,” enabling each of us to “govern” ourselves “from within.”

If we love one another, God abides in us.”

Harry Emerson Fosdick Adventurous Religion and Other Essays

This is what “religion means”: to heed Christ’s call to master ourselves, to develop our best goodness in imitation (“obedience”) to Christ, to seek “spiritual ascendency over ... baser elements.”

Fosdick was no Pelagian. Like his good friend and colleague Reinhold Niebuhr, he acknowledged human sinfulness — not inherited, original sin, but every man an Adam, a sinner in his own right, and even “our best good [is] corroded by egocentricity and pride.” But Fosdick called attention to Jesus’ trust in people, no matter what: “the lost sheep, the lost coin, ... the lost son,” what Fosdick called Christ’s “uncompromising humanitarianism.” Jesus looked for human potential in unexpected places: The Good Samaritan, and the like. Jesus loved people. He calls us to do the same. Love of God will follow, through “that door of human sympathy.”

Fosdick was a moralist, for sure. He was equally an epistemologist. In facing campus skepticism, he exhorted us to faith: going beyond what we’re sure of, with “vision plus daring,” involving oneself in “the greatest adventure to discover here a rational universe” beyond apparent “chaos,” responding to God’s presence with spiritual quest. Fosdick didn’t expect to convince atheists of God’s existence, but he did testify to the adventure of the spiritual search.

So, “how shall we think of God?” he asked. Not by “naïve anthropomorphism.” Not as a guy with a beard, not a king. But also not some materialist mechanism or distant Deist concept. Not something so unsatisfying as “Creative Reality,” not “radically transcendent, ‘Wholly Other.’” He cared not for the creedal doctrine of the Trinity, but he was also no Pantheist. He found “Personality” to be the most adequate symbol of the nature of God, although he acknowledged that theism did not express the fullness of divinity.

Honestly, his most vivid statements about God are these:

1. “Whenever I say ‘God’ I think Christ.” “Sometimes I think I believe in God largely because I cannot help believing in Jesus Christ.”

and

2. “If we love one another, God abides in us.”

And thus, his oft-repeated pastoral prayer: “Eternal God, so high above us that we cannot comprehend thee and yet so deep within us that we cannot escape thee, make thyself real to us today!”28

Fosdick with the Colgate class of 1899

For Fosdick, “personal religion” has “two foci: communion with God and service to [humans].” Both are adventures in character development, how we learn to be the best we can be.

In the “uproar about the teaching of evolution,” Fosdick encountered “the old controversy between science and religion.” As a religious liberal, he saw separate domains for these two epistemic communities. The Bible was full of wisdom but hardly a body of scientific truth. He encouraged his fellow religionists to discern what is truly sacred — spiritual guidance — and what is outdated in their scriptures. Accept the evolutionary truths upon which all of biology is based. Admit the animal identity of humans. Animal origins do not cheapen what humanity is, “with [its] intelligence, [its] moral life, [its] spiritual possibilities, [its] capacity for fellowship with God.”

Science is eminently useful to us all, Fosdick wrote, but religion still challenges our conscience, offers us hope, fosters “brotherliness,” helps us appreciate “life’s meaning as a whole,” and points us to our purpose, including immortality in the face of death. Religion’s beliefs cannot be proved to the skeptic, but they are a “daring outreach and intellectual adventure ... , the mind rising up to think of the Eternal in the noblest terms,” imagining the universe to be “more marvelous” than the “modern materialist” can conceive. He challenged Modernists to consider “belief in amazing truth.”

When we read Adventurous Religion, we can recognize Fosdick’s place in the intellectual spectrum of a century ago: no Fundamentalist, no Modernist, but rather a believer in the spiritual realm, a disciple of Jesus, a moralistic goad with “positive convictions,” a university man with an appreciation for science and a tolerance for diverse views. In short, a Christian liberal, “in earnest about establishing God’s will on the earth,” bent on “reforming Christianity” by recovering “the essential principles of Jesus” for the benefit of a modern scientific age. Being a Christian liberal was an adventure to Fosdick, including an intellectual adventure. As a liberal, “Nothing which can be thought about is too sacred to be investigated by thought.” Liberalism was “a spirit of free inquiry.”29 But he was also a Christian with “abiding convictions” in the “central affirmations of Christianity, the living God, the divine Christ, the indwelling Spirit, forgiveness, spiritual renewal, the coming victory of righteousness on earth, the life everlasting.” Fosdick proclaimed “the two chief aims of Christian liberals” like himself: “To think the great faiths of the Gospel through in contemporary terms, and to harness the great dynamics of the Gospel to contemporary tasks.”

Coda

How to explain Fosdick’s faded fame?

Was he so much a contemporary man of his times, and not for all time?

Do his words — so carefully crafted — fail to address our issues, our values?

Does his liberal Christianity now seem so commonplace to mainline Protestants, that it has lost its adventurous spirit?

Have liberals moved to far more adventurous positions regarding sexuality, race, atheism, etc.? Indeed, have most liberals left Christianity (and religion) behind?

And the Fundamentalists, against whom Fosdick staked his positions? They withdrew from public life after the Scopes trial in 1925, only to reemerge a generation later in 1979 as “values evangelicals,” or “The Religious Right.” They surely have no interest in reading Fosdick now. Indeed, I recently read a 2014 blog entry that calls “God of Grace” “A Hymn Worth Not Singing,” for its author’s “errant theology.”

And us? Students and faculty at Colgate? Could we be made to care about him?

We'll see, as we assess him.

Notes & Sources

- Fosdick, Harry Emerson. “God of Grace and God of Glory” (1930) in Colgate University Founders’ Day Convocation 2017

- Miller, Robert Moats. Harry Emerson Fosdick: Preacher, Pastor, Prophet. New York: Oxford University Press, 1985, pg. 579

- Ibid., pg. 29

- Fosdick, Harry Emerson. The Living of These Days: An Autobiography. New York: Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1956

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Williams, Howard D. A History of Colgate University 1819-1969. New York: Van Nostrand and Reinhold Company, 1969., pg. 225

- Ibid., pg. 228

- Ibid., pg. 230

- Ibid., pg. 231-33

- Ibid., pg. 290

- Miller, Robert Moats. Harry Emerson Fosdick: Preacher, Pastor, Prophet. New York: Oxford University Press, 1985, pg. 38

- Ibid., pg. 41

- Ibid., pg. 39

- Fosdick, Harry Emerson. The Living of These Days: An Autobiography. New York: Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1956

- Ibid.

- Miller, Robert Moats. Harry Emerson Fosdick: Preacher, Pastor, Prophet. New York: Oxford University Press, 1985, pg. 71

- Ibid., pg. 97

- Ibid., pg. 251

- Ibid., pg 45–49

- Fosdick, Harry Emerson. The Living of These Days: An Autobiography. New York: Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1956

- Miller, Robert Moats. Harry Emerson Fosdick: Preacher, Pastor, Prophet. New York: Oxford University Press, 1985, pg. 345

- Ibid., pg. 267

- Fosdick, Harry Emerson. The Living of These Days: An Autobiography. New York: Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1956

- Miller, Robert Moats. Harry Emerson Fosdick: Preacher, Pastor, Prophet. New York: Oxford University Press, 1985, pg. 118

- Ibid., pg. 232

- Fosdick, Harry Emerson. Adventurous Religion and Other Essays. New York and London: Harper & Brothers Publishers, 1926, pg. 244

- Biographical file for Harry Emerson Fosdick, Special Collections and University Archives, Colgate University

- Media collection, A1061, Special Collections and University Archives, Colgate University

- Biographical file for Harry Emerson Fosdick, Special Collections and University Archives, Colgate University

- Biographical file for Harry Emerson Fosdick, Special Collections and University Archives, Colgate University

- Biographical file for Harry Emerson Fosdick, Special Collections and University Archives, Colgate University

- Courtesy of Christopher Vecsey

- Biographical file for Harry Emerson Fosdick, Special Collections and University Archives, Colgate University