By Rebecca Downing

Huntington “Hunt” Terrell built a strong argument for the importance of addressing issues of social justice and human values, ethics, and morality in the liberal arts curriculum — while mentoring generations of students.

1946-1998

If the mark of a genuinely serious philosopher is an unswerving and unembarrassed search for the good and the true, then Huntington Terrell … was an authentic figure in a short line of such dedicated searchers.”

Jerome Balmuth Colgate Scene, March 2002

Huntington “Hunt” Terrell ’46, who taught philosophy at Colgate for 47 years (1951–1998), was known for his “abiding passion for the study and practice of ethics and moral philosophy, especially as these related to his pressing concern for the furthering of universal human rights and personal freedoms.”1

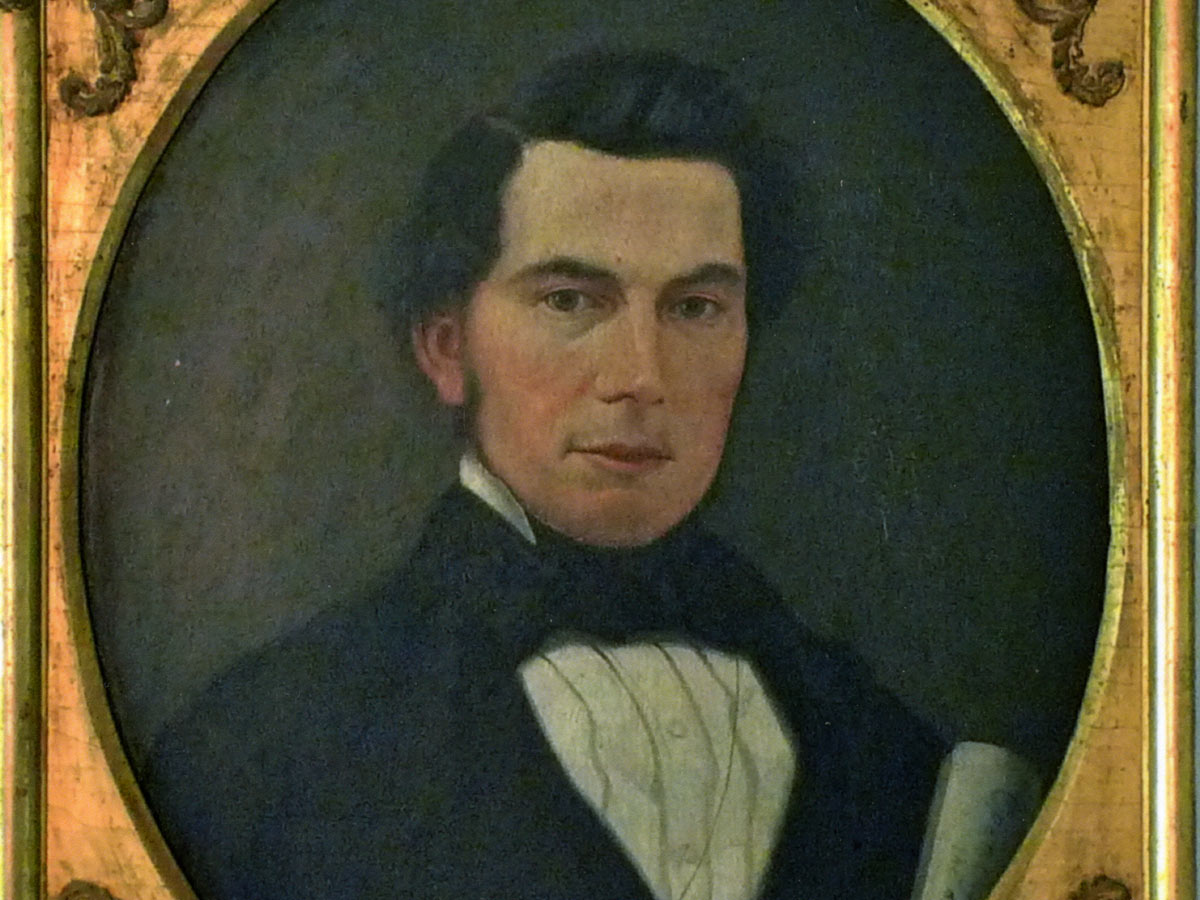

Terrell, circa 1950s

A native of West Hartford, Conn., Terrell first came to Colgate — also his father’s, brother’s, and uncle’s alma mater — as an undergraduate. Although he had entered with the Class of 1946, he graduated within two years, during the university’s wartime accelerated program, in 1944.2 He had majored in philosophy and graduated magna cum laude with honors.3

Brought up in a religious family — his father, William S. (Class of 1917, D.Div., 1942), was head of the Connecticut Baptist Convention and his mother, Marjorie, served as president of the United Church Women4 — Terrell nevertheless developed a “secular passion for justice.”5

After Colgate, he served for two years in the Navy, yet his personal convictions soon led him to a pacifist stance, a dichotomy he continued to wrestle with both personally and publicly during his career.6

Terrell then went on to Harvard for his master’s and doctoral degrees. The subject of his dissertation — the proper standards for “The Concept of a Moral Judgment” — would become the long-standing commitment of both his personal and professional lives.7

He returned to teach at Colgate in 1951. He taught a variety of courses, including Greek Philosophy and Aesthetics, but he used sabbatical leaves at Harvard and Princeton, and in India, to explore contemporary moral theory and practical ethics and the developing discipline of peace studies.8

Throughout his time at Colgate, Terrell built a strong argument for the importance of addressing issues of social justice and human values, ethics, and morality in the liberal arts curriculum.

Influenced by John Rawls’s now classic A Theory of Justice, Terrell sought to extend its ideas internationally, to a theory of universal justice, a society without divisions, borders, or sovereign territories. His idea informed a new course of his own devisement that explored philosophically the link between social and moral problems, Social and Political Ethics, which he taught for many years. His International Ethics course was, according to political philosopher Charles R. Beitz, Class of 1970, “among the first such courses offered in any college in the United States”9 and led to his becoming one of the founding professors of Colgate’s peace studies program (today, the Peace and Conflict Studies Program).10

When controversy over the war in Vietnam erupted on campus, Terrell made himself available to current students as well as alumni, especially to those who sought him out for advice as conscientious objectors and moral protesters. His approach was to help students to gain insight into their motives and explore their rationale and moral stance toward the war and service.11

In addition to his care for students, Terrell also exhibited his love for the campus, donating 37 Norway spruce trees from his property to be planted on Colgate grounds in 1972.12

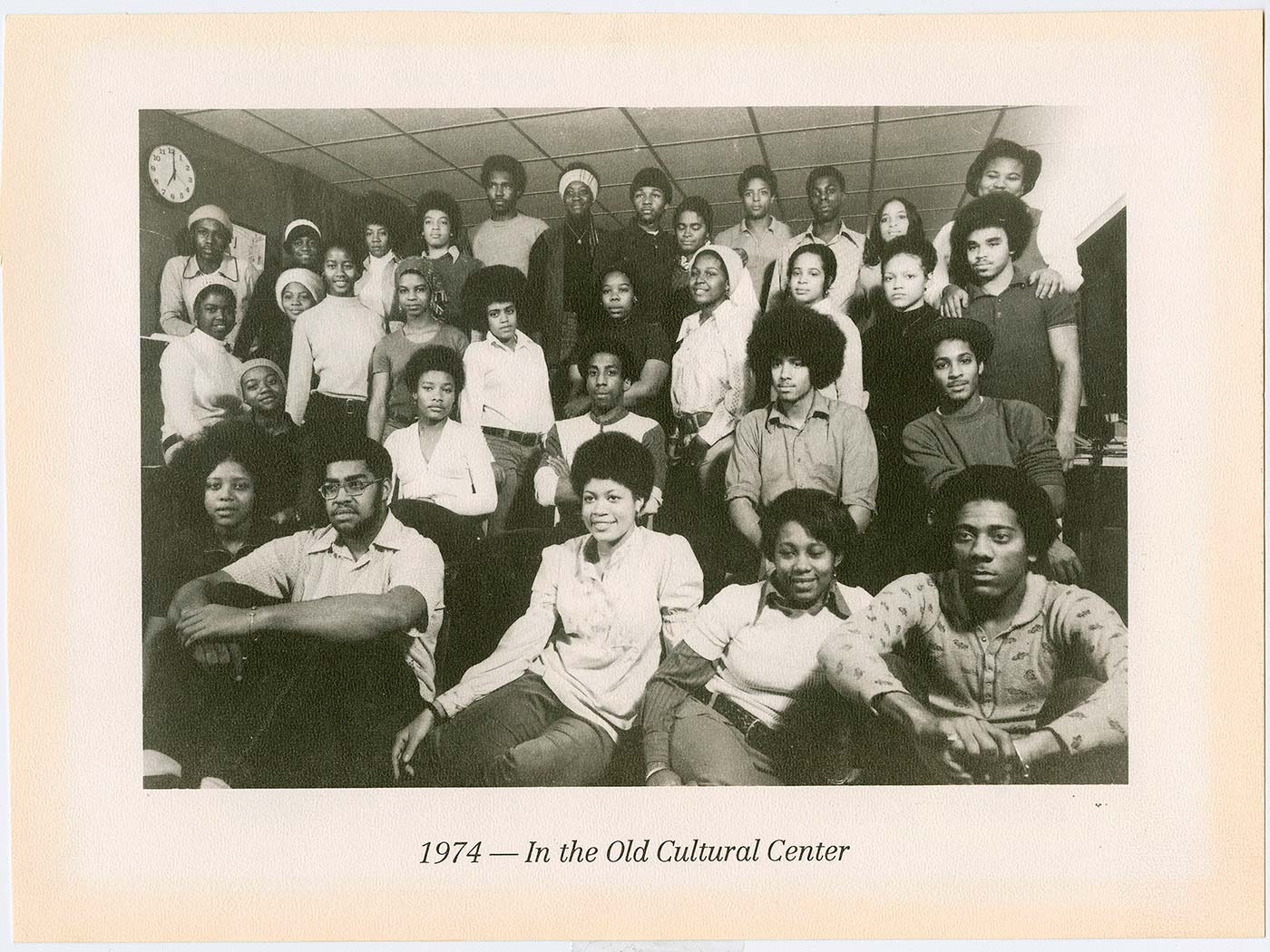

Through teaching as well as action (he was a longtime adviser to the students involved with Bunche House, among other involvements), Terrell “required generations of Colgate students to see the world in a broader and more inclusive perspective than most of us had ever previously known,” said Beitz.13

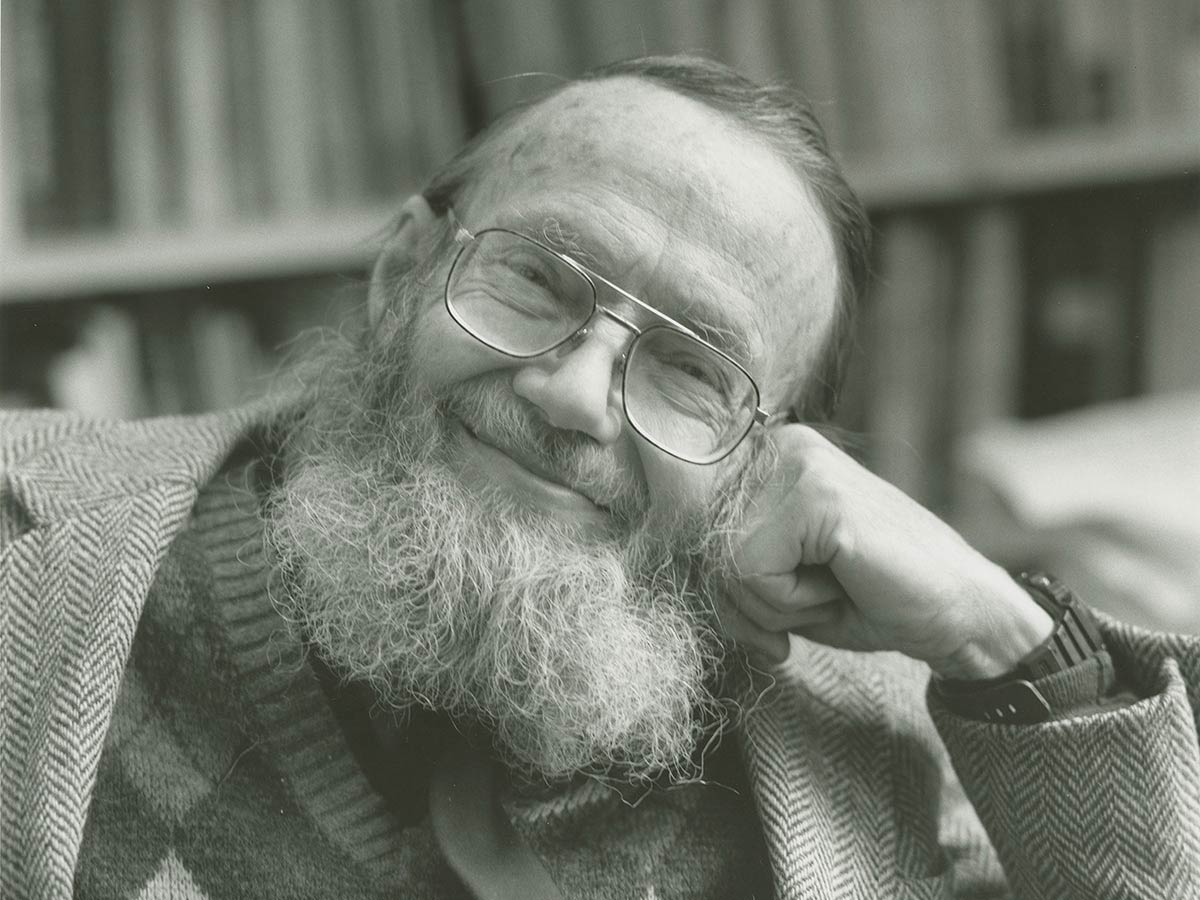

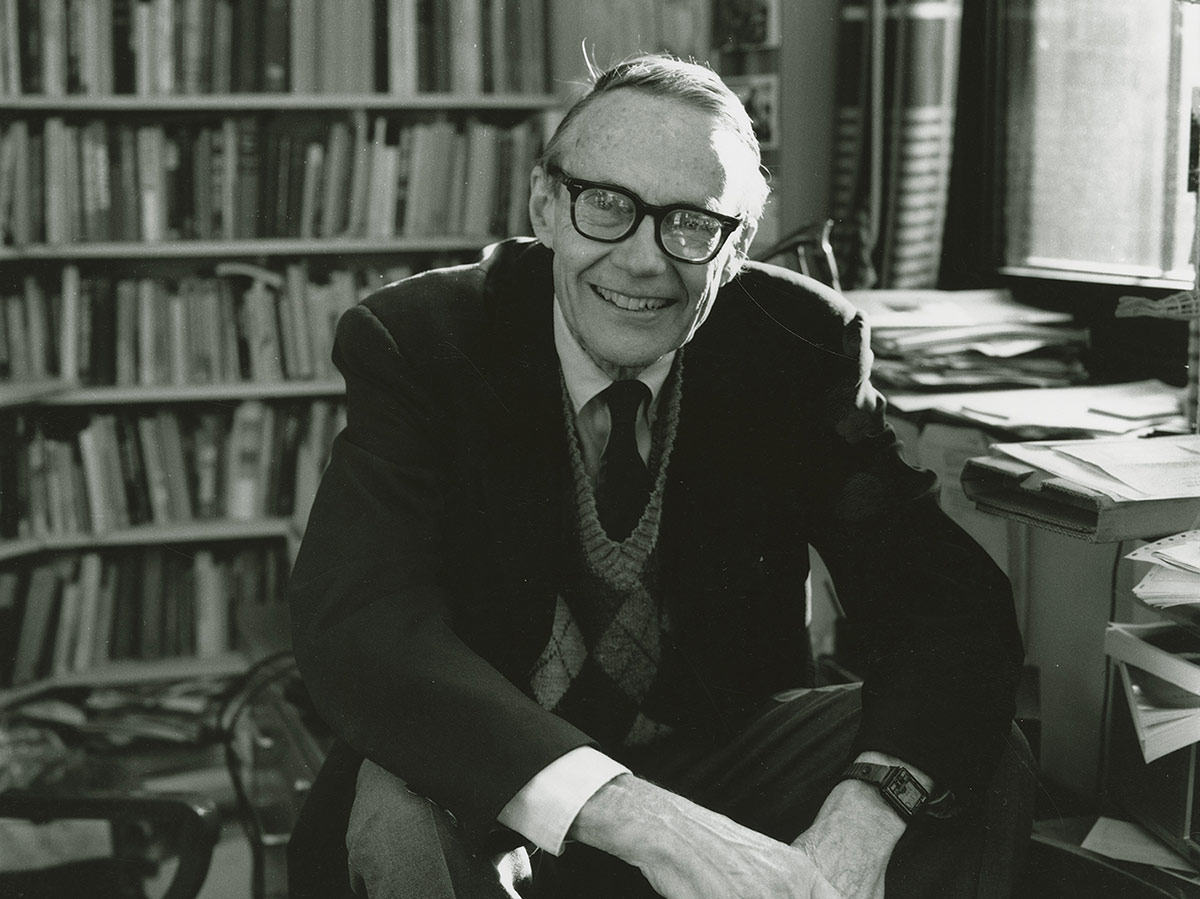

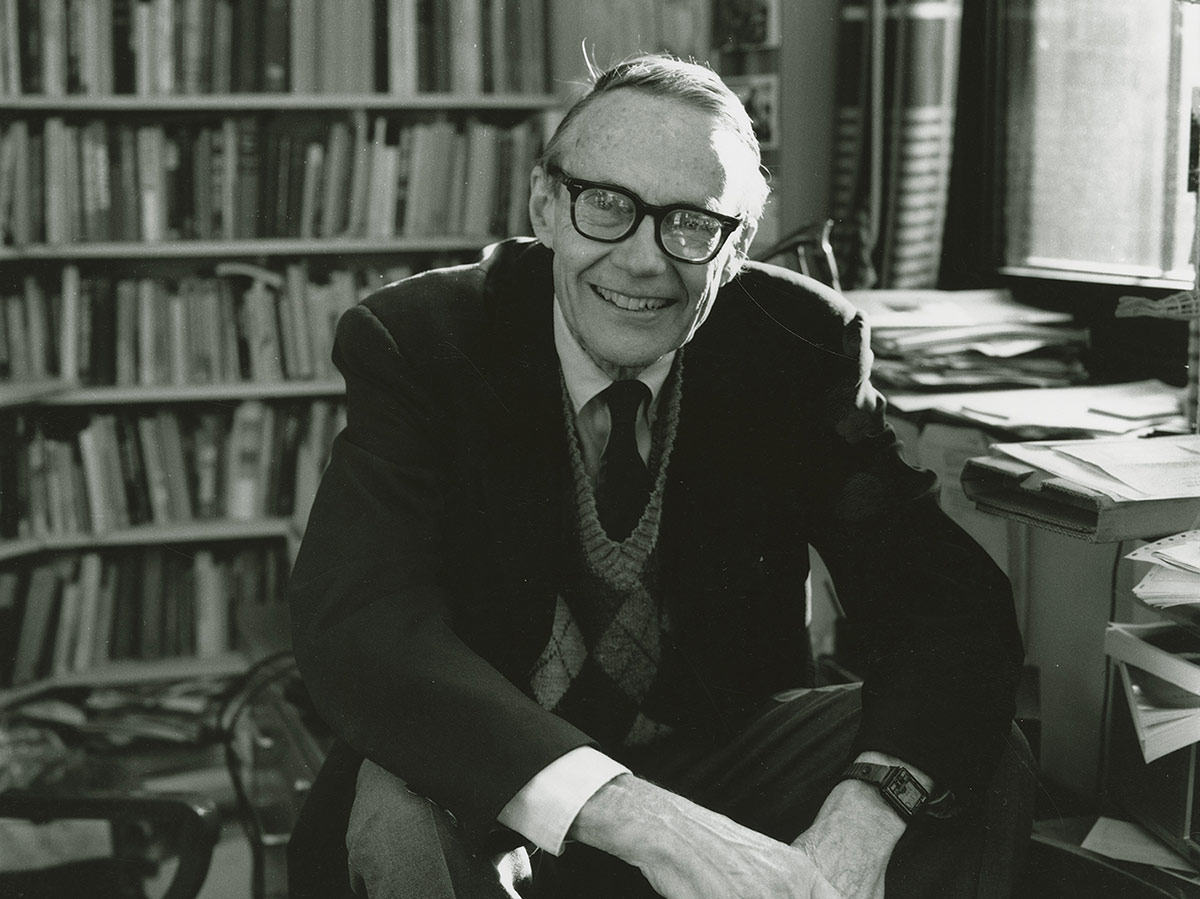

“Hunt” Terrell, circa 1980s. Photograph by John D. Hubbard

In 1986, in the Washington Post’s coverage of the Great Peace March during which 1,000 citizens walked across the country, author Colman McCarthy observed, “The peace movement is now an educated group. In the 1960s, people knew there was something wrong but didn't always have the background to speak intelligently. Students are now coming out who have the skills and analysis. Colgate University is among the 200 peace-movement schools.”14

As Terrell told the reporter, students at Colgate that year had 18 courses to choose from in the peace studies concentration. “A lot of people,” he said, “think the peace-studies students are troublemakers. In fact, they understand the complexities of issues very clearly. We’ve been able to change Colgate for the better because these students have heads and hearts, ideas as well as emotions. They'll be leaders.”15

A true leader himself, among the students as well as the faculty, Terrell received the Alumni Corporation Distinguished Teaching Award in 1994 and the Sidney J. and Florence Felten French Teaching Award. He died on December 29, 2001.

Notes & Sources

Balmuth Quote: Balmuth, Jerome. “Huntington Terrell 1925–2001,” Colgate Scene, March 2002

- Ibid.

- “Colgate mourns the loss of Huntington Terrell, professor of philosophy, emeritus,” Colgate News (blog), January 14, 2002

- Balmuth, Jerome. “Huntington Terrell 1925–2001,” Colgate Scene, March 2002

- Obituary, Hartford Courant, January 27, 2002

- Balmuth, Jerome. “Huntington Terrell 1925–2001,” Colgate Scene, March 2002

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Beitz, Charles R., Class of 1970. “Hail Hunt Terrell,” Colgate Scene, July 1998

- Balmuth, Jerome. “Huntington Terrell 1925–2001,” Colgate Scene, March 2002

- Ibid.

- Gift acknowledgment letter, Colgate Office of Development and Public Relations, Dec. 1, 1972. Biographical file for Huntington Terrell, Special Collections and University Archives, Colgate University

- Beitz, Charles R., Class of 1970. “Hail Hunt Terrell,” Colgate Scene, July 1998

- McCarthy, Colman. “In the '80s, Marching Toward Peace,” Washington Post, November 23, 1986

- Ibid.

- Published in the Colgate Scene, July 1998. Photograph by John D. Hubbard. Office of Communications records, A1009, Special Collections and University Archives, Colgate University.

- Biographical file for Huntington Terrell, Special Collections and University Archives, Colgate University

- Photograph by John D. Hubbard. Office of Communications records, A1009, Special Collections and University Archives, Colgate University.