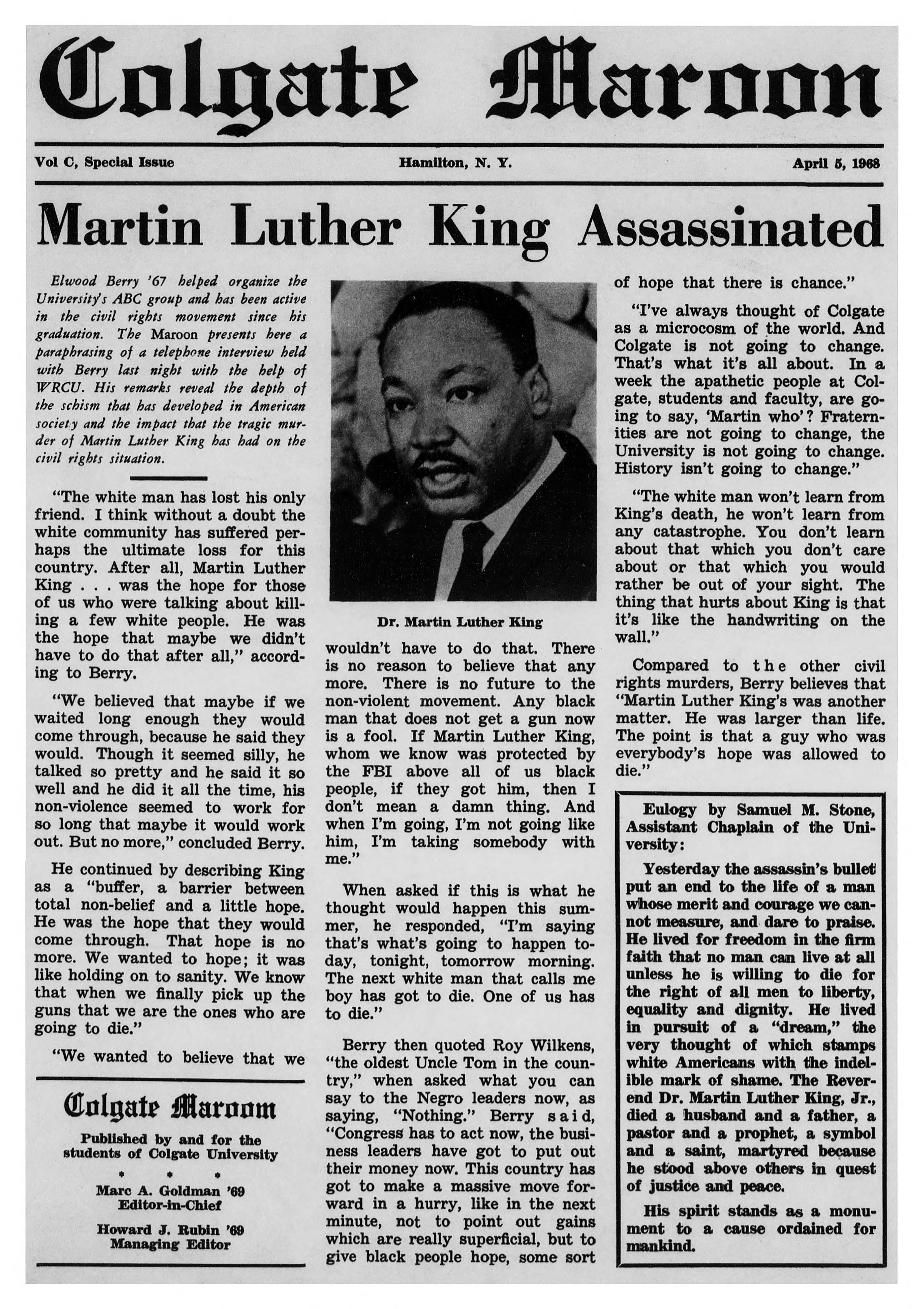

Special issue of the Colgate Maroon upon Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination, April 5, 1968

When activist and civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in Memphis, Tenn., on April 4, 1968, tensions on campus ran high as students vacillated between grief and anger. President Vincent Barnett ordered that classes be suspended and authorized a memorial service to be held at the Chapel.

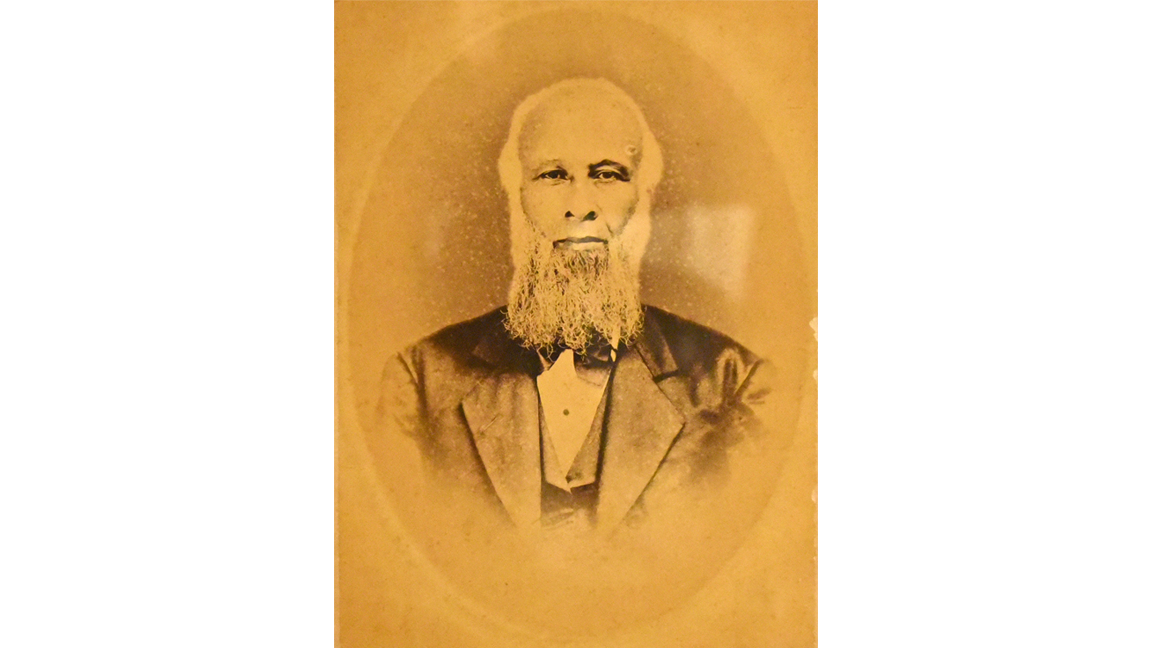

Elwood Berry, Class of 1967 and founder of the Colgate Association of Black Collegians (ABC), was interviewed by campus radio station WRCU that evening. “I’ve always thought of Colgate as a microcosm of the world,” he said. “And Colgate is not going to change. That’s what it’s all about… Fraternities are not going to change, the university is not going to change. History isn’t going to change… [Martin Luther King Jr.] was larger than life. The point is that a guy who was everybody’s hope was allowed to die.”1

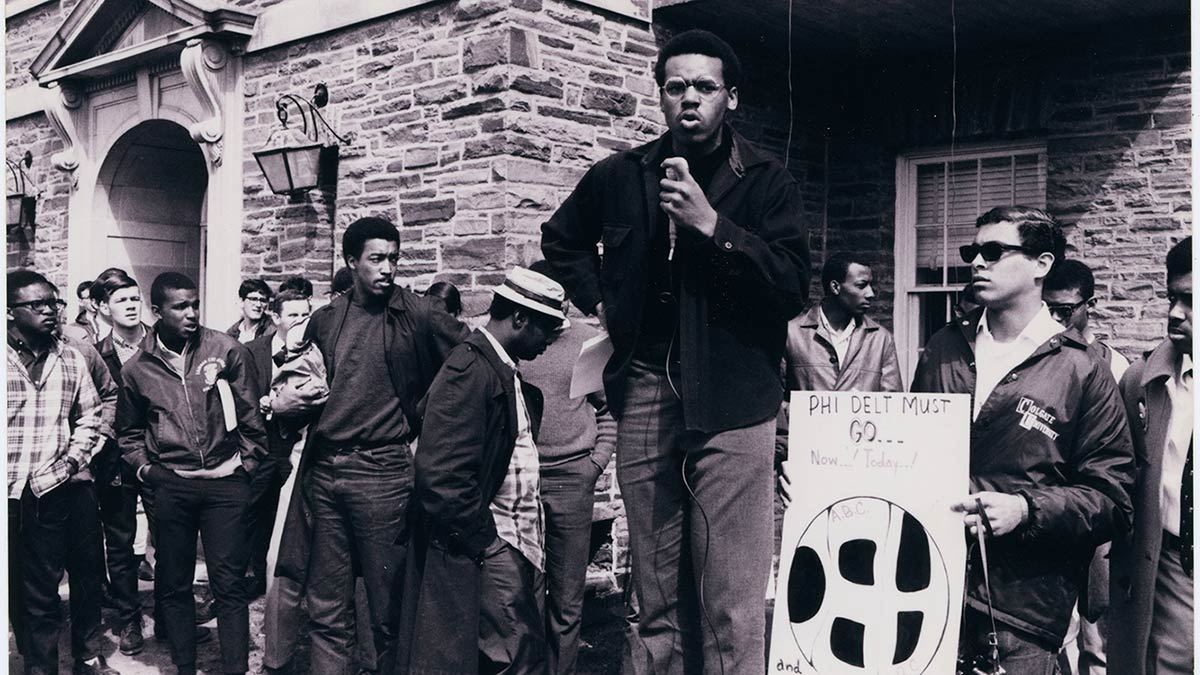

Just a few days later, in the twilight hours of Sunday morning, April 7, 1968, two Colgate students, Robert Boney, Class of 1968, and Naceo Giles, Class of 1970, walked down Broad Street, also known then as Fraternity Row. As the two passed the Sigma Nu fraternity house, someone on the roof shouted racially charged threats. The threats were followed by gunshots. According to Boney, “A window opened up... and I ran behind a tree. A shot was fired.”2 Witnesses corroborated the allegations, adding that the shots fired were blanks. A fraternity member was brought into custody by local law enforcement but never charged; authorities cited a lack of evidence.

Immediately after the incident, members of the ABC began taking action. They first demanded the shuttering and suspension of the Sigma Nu fraternity, and the university complied. The ABC also denounced a second fraternity, Phi Delta Theta, which was believed to practice discriminatory selection procedures.

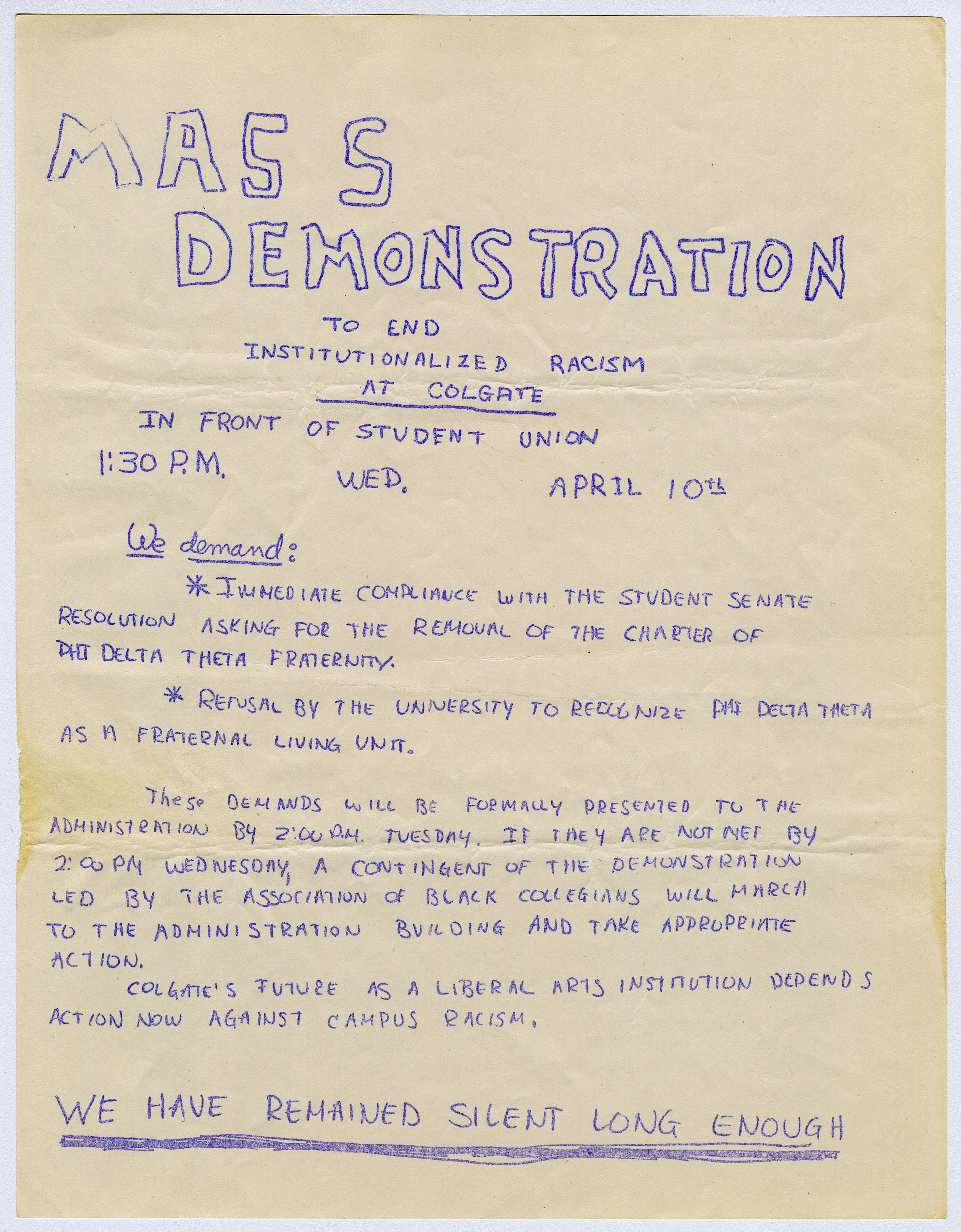

Flyer announces rally on campus, 1968

Indeed, both Sigma Nu and Phi Delta Theta had long held “white gentlemen’s clauses” at the national level, which barred admittance to African Americans, Jewish students, and others.3 While the Colgate chapters argued that they held local autonomy over their ranks, did not practice discriminatory pledging, and were working to change national rules, the incident on April 7 called the seriousness of these efforts into question.

On Monday, April 8, the regular faculty meeting lasted nearly six hours as the faculty passed resolutions attempting to ameliorate ongoing discriminatory issues with the fraternities, including a call for open housing, and to support proposals by the ABC.

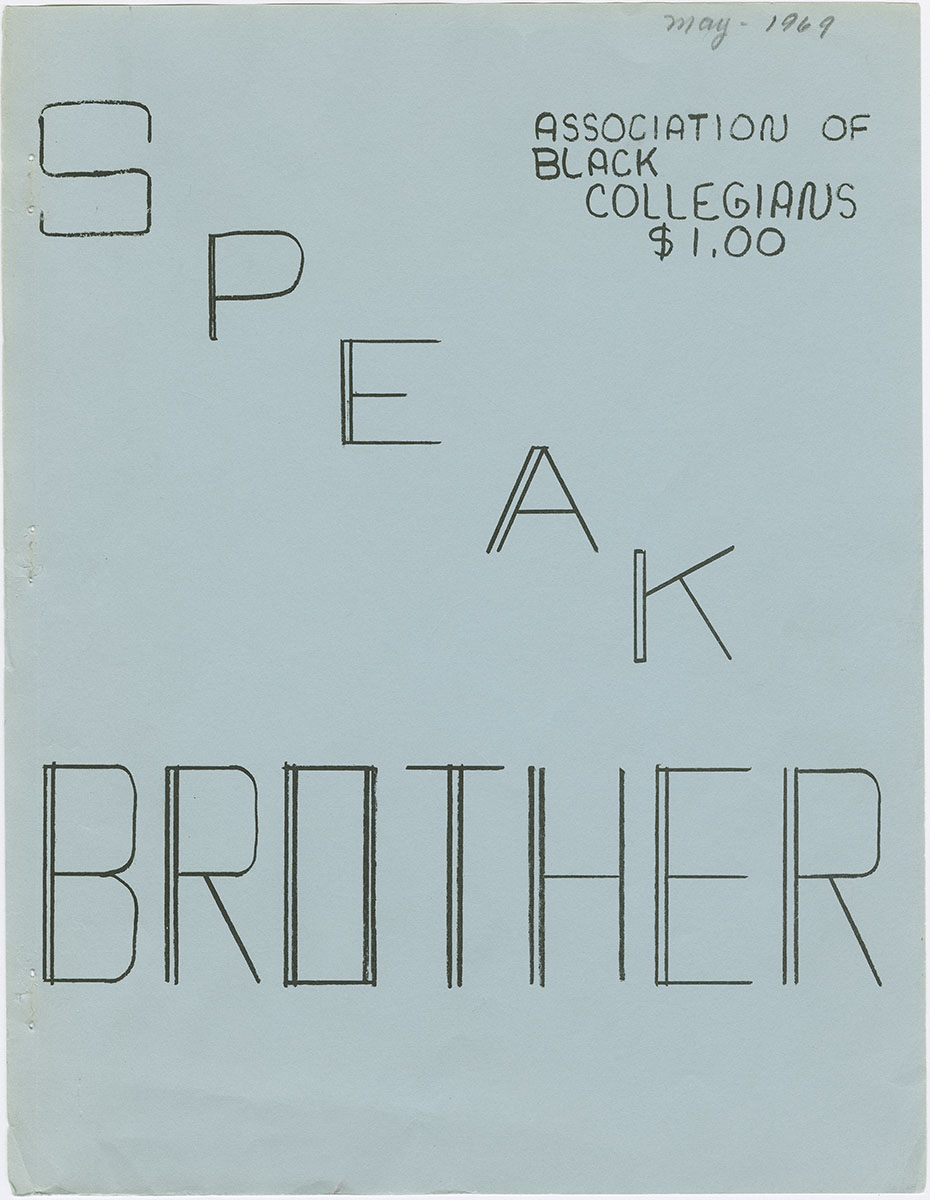

By Tuesday, April 9, members of the ABC called for President Barnett to immediately revoke the charter of Phi Delta Theta and to close the house within 24 hours. Failure to meet their demands would lead to a “direct confrontation with the Administration by the Black people of this community,” they warned.4 Purple mimeographed flyers distributed around campus reiterated these demands and called for a “Mass Demonstration to End Institutionalized Racism at Colgate”; the demonstration would begin with a rally and march from Whitnall Field to the administration building, followed by a sit-in.5

The university did not meet ABC’s demands, and by the afternoon of April 10 the sit-in had commenced. It would last for more than 100 hours. Approximately 400 students and some faculty members peacefully occupied hallways and staircases of the administration building as well as the president’s office. The university served the demonstrators sandwiches, milk, and hard-boiled eggs, while President Barnett and the Board of Trustees discussed how to deal with the demonstrators.

After days of intricate negotiations between the ABC and President Barnett, the sit-in ended at 6:30 p.m. on Easter Sunday, April 14. President Barnett agreed to revoke the Phi Delta Theta charter and to remove all members from the house. As the demonstrators made their way home that evening, they convened once again on Whitnall Field, across from Fraternity Row, and together sang the gospel-turned-protest song “We Shall Overcome.”

Original audio and images from the demonstration, April 1968

Reaction to and fallout from the sit-in was divisive. During commencement weekend, the trustees issued a statement not-so-subtly condemning the sit-in and asserted that those who “disrupt or interfere with the functioning of the University” may be suspended, expelled, and even prosecuted.6 According to editorials in the student newspaper, the Colgate Maroon, student and faculty opinions on the sit-in and its outcome were largely supportive; however, the event spurred the creation of an alternative student newspaper, the Colgate News, whose editors felt the existing Colgate Maroon to be too liberal. President Barnett offered his resignation that summer.

Sigma Nu never returned to campus. In 1976, its house at 84 Broad Street was repurposed as an all-female living unit named Bolton House, which also served as the first women’s center.7 Today, 84 Broad Street is the residence of the Delta Delta Delta sorority. A local chapter of Phi Delt was reinstated in 1970, as the New York Zeta Chapter of Phi Delta Theta.8

The 1968 administration building sit-in kicked off a series of demonstrations and calls for campus change throughout the end of the 1960s and into the 1970s — and beyond. For example, the ABC’s occupation of Merrill House in 1969 eventually culminated in the establishment of the ALANA Cultural Center and the Harlem Renaissance Center. Indeed, as recently as 2014, Colgate students exercised their right to peaceful protest with a sit-in, once again inside the administration building (now the admissions center), seeking action related to “institutionalized racism [and] macro-, and micro-aggressions that have been happening at Colgate and nationwide for a long time.”9

The time is too late. But when the time is too late, the time to act is now.”

John Romano, Class of 1970 WRCU recording, April 10, 1968

Students protest outside Admissions Center, 2014

Professor teaches class during sit-in, 2014

Finally, it is pertinent to note that, although the 1968 sit-in was spurred by the Sigma Nu incident, as well as by the momentum of the national civil rights movement, calls for change related to selective housing on the Colgate campus had begun even earlier. By 1968, students and professors alike had already been fighting this issue for a decade. In the words of John Romano, Class of 1970, during his rallying speech on Whitnall Field, “The time is too late. But when the time is too late, the time to act is now.”10

Notes & Sources

- “Martin Luther King Assassinated,” Colgate Maroon, April 5, 1968

- “Negro Students Seize Colgate Fraternity House,” New York Times, April 8, 1968

- Ibid.

- Stuart T. Infantine, 100 Hours in April: The demonstration, 1968, Protest and Activism collection, A1021, Special Collections and University Archives, Colgate University

- Colgate University Office of the Provost and Dean of the Faculty records, A1003, Special Collections and University Archives, Colgate University

- Infantine, 100 Hours in April: The demonstration

- Jean Walsh, “Bolton House Defines Itself: Offers Plan For All Students,” The Colgate News, September 17, 1976

- Kevin Kinsella, “Phi Delt House Reinstated; New President Given Seat,” The Colgate Maroon, April 24, 1970

- Andy Thomason, “Students at Colgate U. Stage Sit-In Over ‘Institutionalized Racism,’” The Chronicle of Higher Education, September 24, 2014

- Speech by John Romano (digitized audio recording), WRCU records, A1091-00087, Special Collections and University Archives, Colgate University

- The Colgate Maroon and Colgate Maroon News, A1165, Special Collections and University Archives, Colgate University.

- Office of the Provost and Dean of the Faculty records, A1003, Special Collections and University Archives, Colgate University

- Protest and Activism collection, A1021, Special Collections and University Archives, Colgate University

- WRCU records, A1091, Special Collections and University Archives, Colgate University

- Protest and Activism collection, A1021, Colgate University Special Collections and University Archives

- “Martin Luther King Assassinated,” Colgate Maroon, April 5, 1968

- Office of the Provost and Dean of the Faculty records, A1003, Special Collections and University Archives, Colgate University

- Protest and Activism collection, A1021, Colgate University Special Collections and University Archives

- Ibid.